About the CoMSES Model Library more info

Our mission is to help computational modelers develop, document, and share their computational models in accordance with community standards and good open science and software engineering practices. Model authors can publish their model source code in the Computational Model Library with narrative documentation as well as metadata that supports open science and emerging norms that facilitate software citation, computational reproducibility / frictionless reuse, and interoperability. Model authors can also request private peer review of their computational models. Models that pass peer review receive a DOI once published.

All users of models published in the library must cite model authors when they use and benefit from their code.

Please check out our model publishing tutorial and feel free to contact us if you have any questions or concerns about publishing your model(s) in the Computational Model Library.

We also maintain a curated database of over 7500 publications of agent-based and individual based models with detailed metadata on availability of code and bibliometric information on the landscape of ABM/IBM publications that we welcome you to explore.

Displaying 10 of 133 results for "Steffen Fürst" clear search

01a ModEco V2.05 – Model Economies – In C++

Garvin Boyle | Published Monday, February 04, 2013 | Last modified Friday, April 14, 2017Perpetual Motion Machine - A simple economy that operates at both a biophysical and economic level, and is sustainable. The goal: to determine the necessary and sufficient conditions of sustainability, and the attendant necessary trade-offs.

Exploring social psychology theory for modelling farmer decision-making

James Millington | Published Tuesday, September 18, 2012 | Last modified Saturday, April 27, 2013To investigate the potential of using Social Psychology Theory in ABMs of natural resource use and show proof of concept, we present an exemplary agent-based modelling framework that explicitly represents multiple and hierarchical agent self-concepts

Peer reviewed Organizational behavior in the hierarchy model

Smarzhevskiy Ivan | Published Tuesday, June 18, 2019 | Last modified Wednesday, July 31, 2019In a two-level hierarchical structure (consisting of the positions of managers and operators), persons holding these positions have a certain performance and the value of their own (personal perception in this, simplified, version of the model) perception of each other. The value of the perception of each other by agents is defined as a random variable that has a normal distribution (distribution parameters are set by the control elements of the interface).

In the world of the model, which is the space of perceptions, agents implement two strategies: rapprochement with agents that perceive positively and distance from agents that perceive negatively (both can be implemented, one of these strategies, or neither, the other strategy, which makes the agent stationary). Strategies are implemented in relation to those agents that are in the radius of perception (PerRadius).

The manager (Head) forms a team of agents. The performance of the group (the sum of the individual productivities of subordinates, weighted by the distance from the leader) varies depending on the position of the agents in space and the values of their individual productivities. Individual productivities, in the current version of the model, are set as a random variable distributed evenly on a numerical segment from 0 to 100. The manager forms the team 1) from agents that are in (organizational) radius (Op_Radius), 2) among agents that the manager perceives positively and / or negatively (both can be implemented, one of the specified rules, or neither, which means the refusal of the command formation).

Agents can (with a certain probability, given by the variable PrbltyOfDecisn%), in case of a negative perception of the manager, leave his group permanently.

It is possible in the model to change on the fly radii values, update the perception value across the entire population and the perception of an individual agent by its neighbors within the perception radius, and the probability values for a subordinate to make a decision about leaving the group.

You can also change the set of strategies for moving agents and strategies for recruiting a team manager. It is possible to add a randomness factor to the movement of agents (Stoch_Motion_Speed, the default is set to 0, that is, there are no random movements).

…

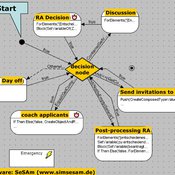

NarrABS

Tilman Schenk | Published Thursday, September 20, 2012 | Last modified Saturday, April 27, 2013An agent based simulation of a political process based on stakeholder narratives

TechNet_04: Cultural Transmission in a Spatially-Situated Network

Andrew White | Published Monday, October 08, 2012 | Last modified Saturday, April 27, 2013The TechNet_04 is an abstract model that embeds a simple cultural tranmission process in an environment where interaction is structured by spatially-situated networks.

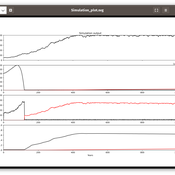

Peer reviewed AgModel

Isaac Ullah | Published Friday, December 06, 2024AgModel is an agent-based model of the forager-farmer transition. The model consists of a single software agent that, conceptually, can be thought of as a single hunter-gather community (i.e., a co-residential group that shares in subsistence activities and decision making). The agent has several characteristics, including a population of human foragers, intrinsic birth and death rates, an annual total energy need, and an available amount of foraging labor. The model assumes a central-place foraging strategy in a fixed territory for a two-resource economy: cereal grains and prey animals. The territory has a fixed number of patches, and a starting number of prey. While the model is not spatially explicit, it does assume some spatiality of resources by including search times.

Demographic and environmental components of the simulation occur and are updated at an annual temporal resolution, but foraging decisions are “event” based so that many such decisions will be made in each year. Thus, each new year, the foraging agent must undertake a series of optimal foraging decisions based on its current knowledge of the availability of cereals and prey animals. Other resources are not accounted for in the model directly, but can be assumed for by adjusting the total number of required annual energy intake that the foraging agent uses to calculate its cereal and prey animal foraging decisions. The agent proceeds to balance the net benefits of the chance of finding, processing, and consuming a prey animal, versus that of finding a cereal patch, and processing and consuming that cereal. These decisions continue until the annual kcal target is reached (balanced on the current human population). If the agent consumes all available resources in a given year, it may “starve”. Starvation will affect birth and death rates, as will foraging success, and so the population will increase or decrease according to a probabilistic function (perturbed by some stochasticity) and the agent’s foraging success or failure. The agent is also constrained by labor caps, set by the modeler at model initialization. If the agent expends its yearly budget of person-hours for hunting or foraging, then the agent can no longer do those activities that year, and it may starve.

Foragers choose to either expend their annual labor budget either hunting prey animals or harvesting cereal patches. If the agent chooses to harvest prey animals, they will expend energy searching for and processing prey animals. prey animals search times are density dependent, and the number of prey animals per encounter and handling times can be altered in the model parameterization (e.g. to increase the payoff per encounter). Prey animal populations are also subject to intrinsic birth and death rates with the addition of additional deaths caused by human predation. A small amount of prey animals may “migrate” into the territory each year. This prevents prey animals populations from complete decimation, but also may be used to model increased distances of logistic mobility (or, perhaps, even residential mobility within a larger territory).

…

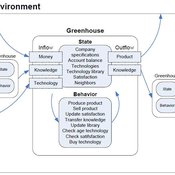

Universal Darwinism in Dutch Greenhouses

Julia Kasmire | Published Wednesday, May 09, 2012 | Last modified Saturday, April 27, 2013An ABM, derived from a case study and a series of surveys with greenhouse growers in the Westland, Netherlands. Experiments using this model showshow that the greenhouse horticulture industry displays diversity, adaptive complexity and an uneven distribution, which all suggest that the industry is an evolving system.

Forager mobility and interaction

L S Premo | Published Thursday, January 10, 2013 | Last modified Saturday, April 27, 2013This is a relatively simple foraging-radius model, as described first by Robert Kelly, that allows one to quantify the effect of increased logistical mobility (as represented by increased effective foraging radius, r_e) on the likelihood that 2 randomly placed central place foragers will encounter one another within 5000 time steps.

Peer reviewed Dynamic Value-based Cognitive Architectures

Bart de Bruin | Published Tuesday, November 30, 2021The intention of this model is to create an universal basis on how to model change in value prioritizations within social simulation. This model illustrates the designing of heterogeneous populations within agent-based social simulations by equipping agents with Dynamic Value-based Cognitive Architectures (DVCA-model). The DVCA-model uses the psychological theories on values by Schwartz (2012) and character traits by McCrae and Costa (2008) to create an unique trait- and value prioritization system for each individual. Furthermore, the DVCA-model simulates the impact of both social persuasion and life-events (e.g. information, experience) on the value systems of individuals by introducing the innovative concept of perception thermometers. Perception thermometers, controlled by the character traits, operate as buffers between the internal value prioritizations of agents and their external interactions. By introducing the concept of perception thermometers, the DVCA-model allows to study the dynamics of individual value prioritizations under a variety of internal and external perturbations over extensive time periods. Possible applications are the use of the DVCA-model within artificial sociality, opinion dynamics, social learning modelling, behavior selection algorithms and social-economic modelling.

This model extends the original Artifical Anasazi (AA) model to include individual agents, who vary in age and sex, and are aggregated into households. This allows more realistic simulations of population dynamics within the Long House Valley of Arizona from AD 800 to 1350 than are possible in the original model. The parts of this model that are directly derived from the AA model are based on Janssen’s 1999 Netlogo implementation of the model; the code for all extensions and adaptations in the model described here (the Artificial Long House Valley (ALHV) model) have been written by the authors. The AA model included only ideal and homogeneous “individuals” who do not participate in the population processes (e.g., birth and death)–these processes were assumed to act on entire households only. The ALHV model incorporates actual individual agents and all demographic processes affect these individuals. Individuals are aggregated into households that participate in annual agricultural and demographic cycles. Thus, the ALHV model is a combination of individual processes (birth and death) and household-level processes (e.g., finding suitable agriculture plots).

As is the case for the AA model, the ALHV model makes use of detailed archaeological and paleoenvironmental data from the Long House Valley and the adjacent areas in Arizona. It also uses the same methods as the original model (from Janssen’s Netlogo implementation) to estimate annual maize productivity of various agricultural zones within the valley. These estimates are used to determine suitable locations for households and farms during each year of the simulation.

Displaying 10 of 133 results for "Steffen Fürst" clear search